The world’s oldest living culture

1. A Girl from the Golden Age

A young mother sits by the riverbank. Behind her the rain-forest rings with the calls of gaudy tropical birds. The baby at her breast is suddenly startled by a movement in the muddy river. His tiny hand reaches out, fingers splayed. Following his gaze, she squints through the glare, always alert to potential danger. Then she gives him a wide, reassuring smile, tossing her blonde locks back over her shoulder. The disturbance among the reeds was just a hippopotamus, sporting in the shallows. Reassured by her smile, the baby’s cornflower-blue eyes droop, and once more he nuzzles against her.

At a safe distance, the infant’s father is chipping flakes from a piece of flint. He is making a scraper. One day its razor-sharp edge will shave the flesh from an animal hide. After that, the old people of the tribe will knead the skin into supple leather. When it has been smoked over a fire to stop it stiffening when wet, it will make a wonderfully soft shawl to stave of those increasingly chilly winter nights.

Further away still, in front of his own hut, one of the tribal elders is entertaining a circle of youths with mythic tales about the origin of their clan. Or are they stories of great heroes and long-dead hunters? His recitation is interspersed with songs that are now irretrievable, and his fair beard moves just like … Well, let’s say, perhaps just like the beard of an Elizabethan Englishman.

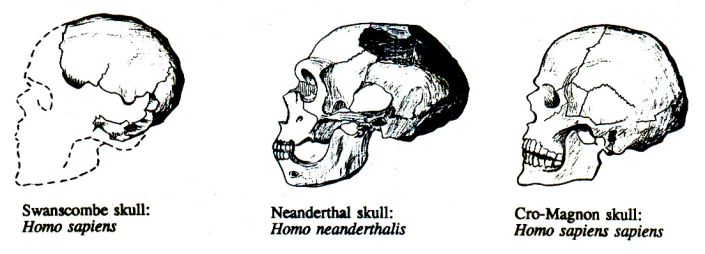

Unfortunately, we’ll never know the full details. A scene something like this occurred beside the River Thames, just downstream from modern London, in the very warm period between the second and third ice ages in Europe. The second (“Mindel”) ice[1] age is thought to have ended about 435,000 years ago, and the third (“Riss”) ice age started perhaps 230,000 years ago. At some time between these eras, a young person died. Anthropologists think that she was female, and about twenty years old. She is referred to as Swanscombe Woman. She is also the earliest-known human being.

The only evidence that she existed is a few fossilised bones from her skull. They were found between 1935 and 1955 in a gravel pit near Dartford in Kent. The greatest anthropologist of the 20th century, Carleton Coon, speculating on these relics, said that they were undeniably human: Homo sapiens. A scientific conference held in 1962 officially concluded that she was a modern human. A cast taken from the inside of the skull proved that her brain was indistinguishable from those of our recent British or Northern European ancestors.

This earliest identified English lass probably lived at some time in the Mindel-Riss Interglacial, between about 435,000 and 230,000 years ago. Her relics were found in a 100-foot stratum of the Thames estuary, together with the remains of various animals of the period. Scientific tests, such as the degree of fossilisation of the bones, confirm this dating. Yet although she lived so long ago, experts have established that her brain capacity was at least 1,270 cc: close to average for a modern European woman.

What did Swanscombe look like?

Reconstructions of the missing parts of her skull suggest that she looked like the much more recent Cro-Magnon people, who were the ancestors of modern north Europeans. They have been described as “… strikingly handsome, fully human, physically superior to most human beings of modem times. The men were well over six feet in height. They had had high foreheads, prominent cheekbones, firm chins. Tall, powerful, splendidly shaped, these ancestral figures seemed like titans out of some forgotten, golden age of mankind.” [2] Less romantically, perhaps, “… a Cro-Magnon man from Europe might well be mistaken for a modern Swede if he walked down the street in Stockholm today.” [3]

What evidence is there for the colour of her hair, skin and eyes?

Psychologist Stan Gooch has written extensively on early humans, arguing that Cro-Magnons must have had fair hair and light eyes [4]. Of course, we can’t be absolutely certain even about Swanscombe’s skin colour, but it is known that pale skin helps to synthesise vitamin D at high latitudes, and for this reason Roger Lewin sums up the prevailing view when he writes that “… long before [Cro-Magnon] times, all European populations would have been white.” [5] The genes for light pigmentation in modern north-Europeans seem to have been passed down to us from our Cro-Magnon ancestors, who in turn presumably received them from their own forebears.

What else can we know about Swanscombe?

Both her cranial capacity, and the impressions left by the brain tissue and blood vessels on the inside of her skull, indicate that she was about as intelligent as we are. The tools used by people of her cultural group suggest that they wore fur clothes. From a site at Terra Amata, near Nice, we learn that they lived in oval huts about 12 by 6 metres in size [6]. Their food included shellfish, elephant, deer, pig, goat and rhinoceros [7]. Jeffrey Laitman of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York has observed that the human vocal tract requires the base of the skull to be arched, and concludes that the capacity for modern speech existed 300,000 years ago. Therefore Swanscombe probably talked to her family and friends – although we may never know more about their language.

What can be learned about the lifestyle of that period?

The climate was warm, and all sorts of game abounded. Fire was used for cooking. Studies of contemporary stone-age tribes show that a full day’s food can be obtained in about two hours of foraging. With less pressure of population, and larger game animals available, the ancient Swanscombe people should have had even more time for social and ritual activities. Although spears were used for hunting, no evidence from this period hints at the existence of warfare. Nor is there any trace of commercial trade. Without the redistribution that a market economy creates, there is little need for a social hierarchy. We may therefore assume that Swanscombe society was egalitarian.

What became of Swanscombe’s people?

About 230,000 years ago, the third ice age began to tighten on Europe. As the weather gradually grew colder, the food sources drifted south. In their wake, people slowly abandoned northern Europe. The ice sheets spread inexorably, and the descendants of Swanscombe Woman were forced to withdraw to the Mediterranean countries, and even beyond – to north Africa, the Middle East and Eurasia. The glaciers covered most of Britain and northern Europe for about 50,000 years. When the ice finally began to melt, the remote ancestors of modem British people returned.

2. When the North Wind Blew

It was a world completely unlike the one we know. A huge ice sheet, kilometres thick, spread out from Scandinavia, burying Europe, Russia and north America until all the northlands resembled today’s Antarctica. Howling winds blew down from the glaciers to the tundra below. Here, a whole belt of the northern hemisphere was sunk in permafrost. Musk-ox, reindeer and arctic fox struggled to survive in this treeless, sodden wilderness. Much further south, starting in protected regions, the tundra shaded into a marginal world of steppe grasslands.

Bison painting from Altamira

Environments like these were typical of the four ice ages that are known to have gripped the northern hemisphere, one after another, for tens of thousands of years at a time. Between these eras of intense cold, the weather in Britain could be warmer than it is now. During one such period, about 230,000 to 435,000 years ago, Britain and northern Europe were inhabited by modern humans like Swanscombe Woman, “sweet as English air could make her”. Then, when the cold conditions returned, her descendants followed the retreating grasslands south and east.

This was the “Riss” ice age. It lasted until perhaps 180,000 years ago. Then, painfully slowly, inch by inch, the glaciers began to withdraw, until after untold centuries there was life in the north once again. Hesitant tribes of our ancestors started drifting back into the lands where Swanscombe’s people had once sunbathed beside tropical rivers.

Very few physical remains of the people who lived and died in this “Riss-Wurm” interglacial period have been discovered. In 1947, G. Henri-Martin excavated a cave in the French valley of Fontechevade. There he found fragments of two human skulls, completely covered by a layer of stalagmite from what had been the cave’s ceiling. They can be reliably dated by the remains of fauna and the stone tools found with them. H. V. Vallois, the French anthropologist who has studied these relics most thoroughly, concludes that there is no difference between them and modern humans [8]. He is also certain that they are part of the same branch of humanity as Swanscombe. The cranial capacity of Fontechevade was about 1460 cc., and the cephalic index was 79. (These measurements correspond closely with those of modem north Germans.)

Until this fortunate discovery, only Neanderthals were supposed to have inhabited Europe during the Riss-Wurm interglacial.

Neanderthal bones were first found in a quarried cave in western Germany in 1856. They were originally thought to have been the remains of a diseased Mongolian who had crawled into the cave to die during the Napoleonic wars. After other remains had been discovered elsewhere, the eminent French palaeontologist, Marcellin Boule, concluded that these Neanderthals were not properly human at all, but an extinct off-shoot of the human family tree. Their brains were large, but with a primitive surface and small frontal lobes. Richard Klein of the University of Chicago sums up contemporary opinion of genetic relations between the two groups: Neanderthals “… contributed few if any genes to modern populations.” [9]

Other than Fontechevade, only tools testify to the presence of our own ancestors in Britain or northern Europe until the coming of the Cro-Magnons. They began to enter during a warmer break in the last (“Wurm”) ice age, maybe as early as 80,000 years ago, trekking after the woolly mammoth and rhinoceros. There they presumably encountered the Neanderthals. What a contrast they must have made!

Neanderthals were short, ugly, chinless and ape-like. Traces of rickets have been found in many Neanderthal bones, indicating either dark skin or inadequate diet. Meanwhile, the definitive Cro-Magnon “…was nearly six foot tall, powerfully built, with a narrow, craggy skull, wide face, square jaw, strong chin and high-bridged nose” [10] The two species seem to have followed their own life-styles and their own destinies. Neanderthals discovered no new techniques, and didn’t adopt the advanced tools of their Cro-Magnon neighbours, like chisels, needles and awls, bone spearheads, and spear throwers. Neanderthals also seem to have been violent by nature. Almost all their remains show broken bones and massive injuries caused by spear wounds. Yet not one has been found killed by Cro-Magnon tools. Few Neanderthals lived much more than thirty years, whereas Cro-Magnons survived well into their fifties.

The Neanderthals became extinct about 35,000 years ago – too soon to witness the amazing changes that our ancestors were to introduce into their bleak, snow-covered world. By 23,000 years ago, a boomerang made from mammoth tusk was in use near what is now Cracow in Poland [11]. Bows and arrows were to follow, invented by some unsung genius in Germany to bring down reindeer. Bone flutes and whistles appeared from France across to Russia between 20,000 and 30,000 years ago. During this period the human population of Europe may have been about 350,000, plus another 80,000 for Russia. After another twelve millennia, this figure perhaps climbed to 950,000, plus another 15,000 in Scandinavia [12].

Although they have been hailed as the most successful hunters of all time, the greatest achievement of the European Cro-Magnon people was to be their art, one of the most glorious triumphs of all human endeavour. In the deepest recesses of their caves these nameless masters ground pigments out of minerals, clay, and charcoal. From simple, static outlines, they quickly learned to use several colours, then to make brushes from chewed twigs, and palettes from bones. In an astonishingly short time they were creating the realistic, unsurpassed masterpieces familiar to us all from cave galleries such as Altamira and Lascaux. At last, in keeping with the restless energy of these people, they stripped the details of their compositions down to the underlying abstract rhythms.

One of the earliest major artworks discovered so far was painted about 28,000 years ago [13]. The greatest masterpieces were created at the very height of the last ice age, about 17,000 years ago, many thousands of years before people in Egypt or the middle east were to take their first crude steps toward any form of culture. Meanwhile, as we shall see, those of our ancestors who had remained outside the frontiers of Europe were beginning their own startling voyage of intellectual and physical discovery.

3. Children of the Sun

For half a million years the British Isles were attached to the European continent. During the last ice age large parts were uninhabitable, but gradually the ice sheets began to withdraw towards Scotland, finally melting away about 9,000 years ago, leaving behind them a tundra that extended from the west coast of Ireland right across to Siberia.

Below what is now the North Sea was a huge low-lying area of fenland, abounding in birds, deer, aurochs, fish and shellfish. This land of plenty was the heartland of our Mesolithic ancestors. If they set their faces to the dawn, they would eventually straggle across their rich fens to the marginal terrains of France, the Low Countries, northern Germany and Scandinavia. Following the setting sun they could trek to the sparsely populated new land that was to become Britain.

Stonehenge, John Constable, 1835

Some of the Children of the Sun did just that. We even have names for the culture-groups that criss-crossed the North Sea plain in those times. But most of them would have seen no reason to leave their fertile homeland. [14]

About 9,000 years ago the sea waters began to rise. Over time the teeming fens of our ancestors were inundated, until the North Sea and the Channel assumed their present forms. Most archaeological traces have been swept slowly away or are lost 30 or 40 meters below the sea. A few implements occasionally dredged up from the Dogger Bank are all that remain of this idyll in our history.

Forced to withdraw to higher lands, our ancestors maintained their generalized northwest European civilization for as long as the new habitats permitted. Those who were stranded in Yorkshire continued the culture known from sites like Star Carr and Flixton I, which are indistinguishable from the Duvensee cultural complex of north Germany.[15] At Star Carr perhaps four families lived in an area of about 240 sq. meters, sleeping on birch twig mattresses beside a lake in the Vale of Pickering. Their animal neighbours included red and roe deer, aurochs, pigs and two breeds of domesticated dog.

A remarkable find at Star Carr was the front part of the skull of a red deer, with antlers still attached. Two eye-holes had been drilled in the bone, turning it into a horned mask. This sacred object was used in some forgotten religious rite, midway in time between the antlered “shaman” figures of cave art and the Horn Dancers of modern Abbots Bromley. It also takes us forward to the neolithic tombs around the great sun temple at Stonehenge, when burials were often accompanied by deer antlers and ox skulls.

Farming of wheat and barley in Britain seems to have begun about 6,700 years ago. Within a very short time the dense oak woods were being cleared for the grazing of cattle and sheep. But long before that, three massive tree trunks were erected at Stonehenge, aligned to the midsummer sunset. Radiocarbon dates from posthole A suggest an age of about 10,100 years. At this time the midsummer sun would have set on “the exact bearing of Post A from the centre of the monument.” [16] Given that the current sarsen (sandstone) monument was built some 6,000 years later, this is evidence of a remarkable religious continuity.

The solar religion of our ancestors was practiced on both sides of the Channel. By at least 5,500 years ago, eight centuries before the Egyptian stone Pyramids, huge collective tombs had been built in every region bordering the old submerged homeland: in Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Holland, Germany, Denmark and Sweden. These were astonishing achievements for people without metal tools. Colin Renfrew is right to stress: “There are no stone-built monuments anywhere approaching them in antiquity”, [17] but even he fails to do them full justice. One of the best known is Maes Howe on Orkney. An entrance passage, oriented to the midwinter sunset and formed of seven-metre slabs, leads to a central burial chamber with a corbelled roof, flanked by three smaller side chambers. The buttressed stone walling of this vault is a brilliant showpiece of the neolithic mason’s skill.

Another outstanding type of sacred monument is the artificial mound, constructed until recent times in Scotland as ”harvest hills.” The greatest is Silbury, a mile from the celebrated West Kennett long barrow. This enormous ziggurat was begun one late summer day (as we know from pollen analysis) around 4,800 years ago. When completed it stood 40 meters high, with a flat top 30 meters across. Containing 250,000 cubic metres of chalk, it took perhaps 20 million manhours to construct — an unparalleled act of piety if, as Aubrey Burl calculates, the immediate community numbered no more than 400 to 500 peoples. [18]

The only comparison is Stonehenge. Sometime around 4,250 years ago, 82 large blue-stones, each weighing four tons, together with 40 lintels, were brought to the site from the sacred mountain of Carn Meini in Pembrokeshire, 217 kilometres away. These were erected in a circle, in radial pairs, spoke-like, in a massive symbol of the sun. The design was then amended and the bluestones moved aside. Seventy-five huge sarsens were hauled from near the even larger sacred complex at Avebury and raised in the formation familiar to us today. Then, about 4,000 years ago, the bluestones were re-erected inside the sarsens.

Who were the People whose devotion to their faith led them to spend centuries building these monuments designed to last for eternity?

A similar physical type prevailed throughout the British Isles. Adult males averaged 5’7″ (171 cm). Women were usually shorter. [19] These were slender people with refined features and long, narrow skulls like their Cro-Magnon ancestors. The population was quite youthful. From a site in Orkney it appears that nearly half were in their twenties. Many of them suffered from arthritis, the scourge of the era. Hardly any had dental caries. We know they ate well: sometimes less than a quarter of the meat was removed from slaughtered cattle.

Their society was more egalitarian than any social order known to history. For thousands of years they lived peacefully, at first in separate family houses, typically 5 meters in diameter, later in massive timber roundhouses which could have housed up to 50 smaller families. The pattern of burials suggests that gender inequality was unknown until late in the period. At Quanterness, “young as well as old were represented in the tomb and women as well as men, in approximately equal numbers.” [20] Lack of specialized occupations would have made class divisions unthinkable. Until the transition to the Bronze Age there is little indication of any hostilities. Even Burl, clinging to an outmoded view of the brutishness of neolithic life, can list only seven cases in which the cause of death may have been human aggression. These deaths might equally have been due to hunting accidents. There is no evidence of warfare.

Estimates of population vary. Castleden’s calculations suggest a total population of 1 million to 1.5 million. This is a surprising figure. The entire British population just before Henry Vlll’s reign is thought to have been no more than 4 million. If both these estimates are correct, then later warlike invaders, racially related but speaking lndo-European languages, could have had little impact on the total gene pool. If so, the faces of the Children of the Sun must reappear today in the features of our own British children.

4. Bell beakers and wild honey

One of the great mysteries in British archaeology began in 1849. In this year John Thurnam, a young doctor, discovered in a hospital museum two skulls that had been excavated from a megalithic grave mound. These timeworn skulls impressed Dr Thurnam so much that he went on to become one of the leading archaeologists of his time.

Thurnam’s own excavations showed that after the long barrows of the neolithic and megalithic periods, a new form of burial began to appear in Britain. The people previously buried had been uniformly slender, with refined features and long, narrow skulls like their Cro-Magnon ancestors. The newer style of barrow, which was round in shape, contained people who had been taller, heavier-boned, and rounder-skulled than their predecessors. Because distinctive bell-shaped drinking cups were frequently placed in their graves, these people became known as the Beaker Folk. Who they were, and what they were doing in Britain, is a mystery that is still unfolding today.

Young woman with bell beaker

Vanished tribes and ancient, eroded tombs often have a mysterious appeal that causes people to project their own romantic dreams on to the spider-haunted past. The Beaker Folk have long proven to be a magnet for strange speculations. Since relatively little is still known about them, it has been possible for writers to interpret the evidence in ways designed to advance their own cultural or political causes.

One of the most influential prehistorians of the 20th century was the Australian Marxist, V. Gordon Childe. In 1925 Childe published The Dawn of European Civilization, which set out his theory that all culture developed in the Middle East, and only later spread into Europe. Childe’s position was made very clear in a 1958 paper [21], in which he argued that European prehistory was nothing but the story of “the irradiation of European barbarism by Oriental civilization”.

For several decades this became the standard view, and it was projected onto the mysterious Beaker Folk. The impression given in many older histories is that they arrived in Britain as noble warriors and traders about 4,000 years ago, set themselves up as a ruling elite, systematically destroyed the indigenous religion in favour of their own – whatever that may have been – and taught the locals how to use metal, thus ushering in the early Bronze Age.

According to a 1967 account [22], “…the Beaker Folk would step ashore, proud strangers in fine woven coats, carrying quivers of arrows on their backs and gleaming bronze daggers at their sides.” They “… must have seemed outlandish to many of the … peasants [sic] whom they passed among” [23]. They were “… energetic conquerors ruthlessly dispossessing the Neolithic communities of their best pastures, and also no doubt of their herds, and sometimes of their women”.[24] By 1973 these bringers of light into the allegedly dark world of Britain had even been transformed into inter-planetary space travellers [25].

We now know that hardly any of this was true. Radiocarbon and other modern dating methods have disproved the idea that anything worthy in our prehistoric past came from the middle east. We know that our megalithic tombs are the oldest stone monuments in the world. We know that our ancestors had a well-developed solar religion that expressed itself – among other ways – in exquisite sacred architecture. We know that this religion lasted for at least 6,000 years. We know that our ancestors had no concept of class or gender inequality. It has even been suggested that they were in the process of developing their own form of writing [26]. We know that the British population at the time may have been l million to 1.5 million. Yet in the 1950s and ’60s, textbook after textbook asked us to believe that the high civilisation of our ancestors was overwhelmed by a bunch of plundering rapists from the east.

The picture that is now emerging suggests that the Beaker folk probably arrived in a few small, peaceful groups. Fragments of beakers have been found in the very last stages of construction of the sacred complex at Avebury, indicating that the newcomers helped in its building. They seem to have blended in well. Harding [27] points out that: “Other aspects of Neolithic life evidently continued unabated, or even enhanced by Beaker-using communities.” Renfrew [28] flatly rejects any concept of a Bell Beaker “invasion”.

These scattered immigrants were probably of the physical type that some ethnologists call Dinaric. People of this stock are common today in the Balkans and the Tyrol. As Baker [29] points out, they are often fair. Their physical impact on the British population was negligible. Some relict individuals with skulls similar to those of the Beaker Folk were studied in the 1930s in Angus, Kincardine and Aberdeenshire [30]. They didn’t look at all “foreign”.

What of the claim that the Beaker Folk introduced metallurgy to the British Isles? Experiments by Richard Thomas of the University of Wales suggest that early Bronze Age tools in Britain were smelted using a simple bonfire-type process, and that there were no significant changes in the methods of metal-working around the time of the Beaker settlements. Reviewing the recent evidence, Paul Budd [31] concluded, “I am sure that Beaker Culture metallurgists from the Rhineland never stalked the [British] countryside in search of ores to make [metal artefacts]”.

Then what impact did the Beaker Folk have on our heritage? It has occasionally been suggested that they may have brought the first Indo-European language to the islands of the North Atlantic. If so, as Mallory [32] tersely comments, it was “… not one that evolved into anything for which we have evidence”. There is, however, one hint as to why these newcomers were apparently accepted and even welcomed. Burl [33] argues that they may have been masters of the art of fermenting honey with wild yeast to make mead. He cites evidence that a beaker found in a Scottish grave contained residue of lime-honey, as well as the herb meadowsweet, which would have given the powerful alcoholic drink “an agreeable taste and smell”.

As Marxist ideology has waned, younger archaeologists have debunked the myths fabricated about the Beaker Folk. They didn’t look very different from the rest of the British population. There were few of them. And all that we can be sure they added to the high culture of our ancestors was a new type of wine cup.

5. Age of Iron

At the end of the last Ice Age sea levels rose, flooding the fertile and abundant North Sea Plain under a shoreless foam. Our ancestors were forced to spread out into the harsher lands of Britain, north-western Europe, and Scandinavia. There, they continued to live in peace and equality. Yet by the first millennium BC the Atlantic culture that had lasted so long was about to be shattered.

Nomadic descendants of our ancestors had also moved far across Europe, penetrating the Russian steppes, Central Asia, Siberia – and perhaps even reaching the Americas [34]. For reasons that are still obscure, this contact with Asia traumatised their culture.

From about 5000 years ago, in the Volga region northwest of the Caspian Sea, we begin to see the emergence of a socially stratified and militaristic society, often known as the Kurgan or Corded Ware culture. As this society expanded, stone-built defensive ramparts came to be needed (as at Mikhailovka on the Dnieper). Battle axes were buried in rich graves, along with wagon wheels, and silver, gold and copper implements. The people who were interred are presumed to be the first known speakers of Indo-European languages.

Statue of Vercingetorix, Burgundy, France, 1865

We know what they looked like. Hundreds of burials from southern Russia have been excavated. The people “… are predominantly characterized as late Cro-Magnons with more massive and robust features than the gracile Mediterranean peoples of the [Balkans]. With males averaging about 172 centimetres in height they are a fairly tall people within the context of Neolithic populations.” [35]

By the time that the last features were being added to Stonehenge, eastern militarism had spread to central Europe. The Unetice culture, which reached from Czechoslovakia to Poland and north Germany, was characterised by princely tombs, with possible signs of an emerging warrior caste.

Warfare, military camps, heavy fortifications, and new weapons spread like an oriental plague. All over Europe, our ancestors were forced to adapt. Even in Britain, the long millennia of equality and peace ended with the rise of the first native chieftainly culture, in Wessex.

By perhaps 770 BC a startling new culture, known as Hallstatt after the famous cemetery near Salzburg, had arisen in central Europe. The founders of Hallstatt are the earliest descendants of our ancestors whose name has been preserved. They were called Celts.

Also for the first time, we have a written description of their appearance. Herodotus, writing in about 450 BC, describes them as tall, fair-skinned, and blond, with blue eyes. Modern excavations confirm Herodotus’ observations: the skeletons disinterred from Hallstatt are indistinguishable from their contemporaries in north Germany [36], where even today these characteristics are common.

The Greeks made no distinction between Celts and Germans. They “…regarded the Germans and Celts as close kin, very similar in physical features, manners and customs.” [37] In fact, “the Germanic peoples first emerge into recorded history in the Roman Acta Triumphalia for the year 222 BC” [38], fighting as allies of a Celtic army at Clastidium.

Hallstatt had been founded on the local salt-mining industry, which was vital to prehistoric societies. By sophisticated trade as-well as military conquest, the culture of the Celts was to develop into the most advanced in Europe, and to expand as far as France, the British Isles, Spain, the Mediterranean, and Anatolia.

Theirs was a warrior society, adept at building massive fortifications such as the Heuneberg overlooking the Danube, or Crickley Hill in Gloucestershire. Brilliant metallurgists, the Celts were to pioneer the casting of iron tools – and, ominously, iron weapons. As Chapman points out, the very name “Celt” may be related to the Old Norse “hildr”, meaning “war”.

Ammianus Marcellinus left us a Roman stereotype: “Almost all the Gauls are of tall stature, fair and ruddy, terrible for the fierceness of their eyes, fond of quarrelling, and of overbearing insolence. In fact, a whole band of foreigners will be unable to cope with one of them in a fight, if he call in his wife, stronger than he by far and with flashing eyes …”

Celtic militarism – culminating in the sack of Rome in 390 BC, and the plundering of the holiest site in Greece, Delphi, in 279 BC – should not obscure other aspects of their culture, like their art, technology and religion. These can be studied in any number of textbooks and museums.

One thing that contact with the east had not erased was the old European respect for women. The tomb of the young princess at Vix, near the Mont Lassois hillfort, contained the richest grave goods yet discovered in prehistoric Europe. Perhaps this confirms Tacitus’ statement regarding Boadicea: “Britons make no distinction of sex in their appointment of commanders.” And here is Cassius Dio Cocceianus’ description of the warrior-queen: “She was enormous of frame, terrifying of mien, and with a rough, shrill voice. A great mass of bright red hair fell down to her knees: she wore a huge twisted torc of gold, a tunic of many colours, over which was a thick mantle held by a brooch.”

Celtic implements begin to appear in the British Isles from about 500 BC, but they don’t necessarily imply any large-scale movement of people. The earliest clear evidence of an immigrant Celtic colony in Britain comes from the Arras culture of east Yorkshire. Many cemeteries have been discovered in this region, in addition to the famous chariot burial at Garton Slack in the eastern Wolds. The Arras culture dates from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BC.

The elusive Picts had begun founding settlements in Ulster by the 4th or 3rd century BC. Hubert [39] identifies the Picts with the Gaulish tribe of Pictones mentioned in Roman sources. Groups of Goidels settled in Ireland, where they became known as Scotti – a Gaulish word that probably means “skirmisher”.

Probably the most disruptive incursion of Celts into Britain occurred in the 1st century BC, shortly before Caesar’s raids. Belgic Gauls seem to have invaded south-east England, perhaps in two separate waves, which were resisted by more assimilated Celtic tribes such as the Catuvellauni. These Belgic invaders are usually associated with the appearance of cremation graves in Kent.

By 55 BC, Celtic tribes may have accounted for “as much as two thirds of the population” of mainland Britain [40]. The vast majority of the tribesmen, however, were probably descendants of the Swanscombe people, who had adopted a Celtic language, together with the artistically brilliant but ferociously martial culture that dominated Europe in the age of iron.

6. Island of angels and poets

Pope Gregory (590-604) once observed some ethereally beautiful children in the streets of Rome. Struck by their radiant looks, he asked what tribe they belonged to. They answered that they were called Angles. “It is well, ” he said, “for they have the faces of angels, and such should be the co-heirs of the angels of heaven. “

But the Angles were not unknown to Rome. In the first century, Tacitus had described some of the religious customs of the continental Angles in his Germania. In the meantime, much of this Germanic tribe had migrated across the North Sea.

Several reasons for the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain have been suggested. One factor may have been the expansion of the Huns, a Turkic-Uighur people from central Asia. In the 4th century CE they swarmed across the Russian steppes, crossing the Volga in about 370 and eventually establishing a huge empire of their own centred on what is now Hungary. This Asian incursion forced nations that were already established in the region, such as the Goths, to move west, to the Balkans and beyond, in an early form of “White Flight”. No doubt population movements of this order set up a ripple effect across Europe.

Anglo-Saxon harpist (re-enactment)

Any additional pressure on the environment of the North Sea coastal regions would have been disastrous for the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. Much of their land was coastal bog or sand-dune. What thin soil they had was becoming increasingly marshy. From the 2nd century on they responded by building artificial islands (“terps”), but these quickly became overcrowded. Emigration was the only possibility, and the Hunnish invasion of Europe may have blocked their traditional outlet to the south, into what is now the German state of Saxony.

Furthermore, Roman authority had collapsed. On 24 August 410, the starving City of Rome had surrendered to Alaric, King of the Visigoths, among whose bounty was the sister of the emperor. Unable to defend even itself, Rome had no troops to spare elsewhere. Emperor Honorius told the Latinised Celts in Britannia that they would have to stand alone against the increasing ravages of the Picts and Scots.

A local militia was set up, but “Without a paid Roman army and a paid Roman civil service, there was no longer a need for Roman currency, so the supply of new coins from Roman mints on the continent quickly dried up. Without the need to equip, feed and clothe the troops and officials of the Empire a whole range of urban crafts in metal, bone and leather died or decayed. The cities of Roman Britain had always been artificial creations superimposed upon an Iron Age economy; all now went into rapid decline.”[41]

With their own lands flooding and over-crowded, the Anglo-Saxons had to move somewhere. In Catherine Hills’ laconic words, “Eastern England is not far from the other side of the North Sea and the attraction of an agriculturally rich land with an apparently dissolving political and administrative system would have been hard for the coastal people to resist.”

According to Bede (writing in 731), the Romano-British ruler Vortigern, under attack from the Picts and Scots, hired Anglo-Saxon mercenaries. Three shiploads of men under Hengest and his brother Horsa landed at Ebbsfleet in 449. After a dispute about working conditions, they brought over reinforcements from the continent and overran Kent. While there is no hard evidence for this legend, it is not improbable. Rome hired Germanic warriors to defend the provinces, and Vortigern may have copied the imperial ways.

Bede also said the English of his day were descended from “the three most formidable races of Germany”: the Saxons from Old Saxony, the Angles from Angeln (Schleswig-Holstein) and the Jutes from Jutland in Denmark. For many years this seemed too simplistic, but recent excavations confirm Bede’s account. Pottery, metalwork and brooches excavated between the Elbe and Weser rivers resemble similar items found in Saxon cemeteries in England. Likewise, grave goods found in Schleswig and Fyn have their “Anglian” parallels in sites such as Caistor-by-Norwich.

What Bede does not tell us is that Germanic visitors were settling in Britain long before the time of Hengest. A Germanic cemetery near Winchester has been dated to the mid-fourth century. This is hardly surprising. The only difference between the Celts and the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, was cultural. By this stage they spoke different languages and followed different religions. The British Celts were mostly Christianised, while the newcomers clung to the faith of their fathers.

We know from the names of the days of the week and from place-name evidence that the Anglo-Saxons worshipped Tiw, Woden, Thunor and Erig. A surviving charm invokes an Earth Mother, who may be the Nerthus worshipped by the continental Angles in the first century. The epic poem Beowulf refers to the god and goddess known later in Scandinavia as Heimdall and Freya. The third and fourth months of the year were named after two more goddesses, Hretha and Eostre (modern Easter).

Older scholars portrayed the Anglo-Saxon settlement as a brutal military invasion, after which the defeated Celts fled to Brittany, Wales and the far-western parts of modern England. This now seems unlikely. “Careful examination of the location of early Anglo-Saxon settlement and place-names suggests that the course of events varied from region to region. In Sussex it looks as if there may have been a division of the land by treaty, since all very early Anglo-Saxon sites lie in a group between the rivers Ouse and Cuckmere, [42] as if the immigrants had been granted that particular area to settle.” Excavations show that many of the new settlers married and were buried with Celtic women, which hardly suggests genocidal warfare [43]. Nor does the fact that early Anglo-Saxon kings married into Celtic royalty. For instance, lda, the founder of Northumbria, formed an alliance with Culvynawyd and married his daughter – Bun or Bebban. Bamborough, the greatest Northumbrian fortress, is named after this princess – showing that relations between native Celts and Anglo-Saxons were not always hostile.

It also indicates the respect for women shown by all the northern peoples. Women could exercise independent regal powers, as Queen Seaxburh did in Wessex from 672-3. Even in the tenth century, Aethelflaed, Queen of Mercia, ruled in her own right from 911-18, leading successful campaigns against the Vikings of York. [44]

Magnificent jewellery and metalwork are often thought of as the chief heritage of Anglo-Saxon times. But England was no dark, war-torn land at the edge of the world. Aethelberht of Kent married Bertha, daughter of the King of Paris. Pope Gregory wrote often to the couple. Needing a teacher at his royal court, Charlemagne turned to Alcuin of York. Anglo-Saxon scholarship was renowned: “English schools excelled all those of Europe, and English scholars eclipsed their continental contemporaries in all fields of scholarly endeavour, their writings forming the staple of the European school curriculum for many centuries to come.” [45] In a sign of things to come, “England produced the most extensive vernacular literature of any country in Europe during the early Middle Ages, with a particular emphasis on poetry” [46]

[2] Robert Silverberg, The Morning of Mankind, N.Y., l967

[3] F. Clark Howell, Early Man, Time-Life, N.Y., 1973

[4] see Total Man, 1972; Personality and Evolution, 1973; and The Neanderthal Question, 1977

[5] Roger Lewin, In the Age of Mankind, Washington, 1988

[6] Desmond Collins, The Human Revolution: from Ape to Artist, Oxford, 1976

[7] Marie-Louise Makris (ed), The Human Story, Hong Kong, 1989

[8] H. V. Vallois, The Fontechevade Fossil Men, American Journal of Physical Anthropology 7: 339-362

[9] Stan Gooch, however, claimed that modern non-European populations may have 50% or more Neanderthal genes. Modern genetic studies suggest that very few, if any, Neanderthal genes have found their way into our gene-pool.

[10] John Geipel, The Europeans, Longmans, 1969

[11] See Nature, October 1987

[12] Desmond Collins, Palaeolithic Europe, Devon, 1986

[13] See New Scientist, 5 December 1992

[14] R.M. Jacobi, “Britain Inside and Outside Mesolithic Europe,” Proc. Prehist. Soc. 42 (1976).

[15] K. Bokelmann, “Duvensee, ein Wohnplatz des Mesolithilikums in Schleswig-Holstein, und die Duvesengruppe”, Archäologische Information, l (1972)

[16] Rodney Castleden, The Stonehenge People, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1987

[17] Colin Renfrew, Before Civilization: The Radiocarbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe, Cambridge, 1979

[18] Aubrey Burl, Prehistoric Avebury, Yale University Press, l979

[19] G. Billy calculated the heights of both his male Cro-Magnons, I & lll, to be l7l cm., with female Cro-Magnon ll being 166 cm.

[20] See “Colin Renfrew” in Current Archaeology, Vol. 9, No. 5, I986

[21] V. Gordon Childe, “Retrospect”, Antiquity, 32: 70

[22] Robert Silverberg, The Morning of Mankind, N.Y., 1967.

[23] John Geipel, The Europeans, Longmans, 1967

[24] J. & C. Hawkes, Prehistoric Britain, London, 1947

[25] T. C. Lethbridge, The Legend of the Sons of God, London, 1973

[26] Rodney Castleden, The Stonehenge People, London, 1987

[27] Dennis Harding, Prehistoric Europe, Phaidon, 1978

[28] Colin Renfrew, Archaeology and Language, Jonathan Cape, 1988

[29] John Baker, Race, Cambridge, 1976

[30] See letter by Howard K. Jones, Current Archaeology, Vol X No 4, 1988

[31] Paul Budd, “Recasting the Bronze Age” in New Scientist, 23/10/93

[32] J. P. Mallory, In Search of the Indo-Europeans, Thames & Hudson, 1991

[33] Aubrey Burl, Prehistoric Avebury, Yale, 1979

[34] Nigel Davies, Voyagers to the New World, London, 1979

[35] J. P. Mallory, In Search of the Europeans, London, 1989

[36] John Baker, Race, Cambridge, 1976

[37] Malcolm Chapman, THE CELTS – The Construction of a Myth, London, 1992

[38] P. B. Ellis, Celtic Inheritance, London, 1985

[39] Henri Hubert, The Greatness of the Celts, London, 1987

[40] Frank Delaney, The Celts, London, 1986

[41] Nicholas Brooks, in The Making of England: Anglo-Saxon Art and Culture, British Museum Press, 1991

[42] Catherine Hills, “The Anglo-Saxon Settlement of England”, in The Northern World, London, 1980

[43] John Baker, Race, Cambridge, 1976

[44] See Williams, Smyth & Kirby, A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain, London, 1991

[45] Michael Lapidge, “The New Learning”, in The Making of England

[46] Janet Backhouse, “Manuscripts”, in The Making of England